Results of this research reported in the Harvard Business Review support many of the age-old axioms of successful fundraising. Sharing this article with board members and volunteer fundraisers at your next orientation or training meeting may prove to be very effective. Too often, volunteer fundraisers are overly fixated on objections and failures. This article readily identifies that we tend to focus too intently on our own feelings, and this creates unfounded apprehension. Quite simply, this research demonstrates that people have far greater influence than they realize. There is great power in a simple direct request. People actually say ‘yes’ more frequently than the asker anticipates. And what about involving a little social pressure to our next ‘ask’ for annual support? This article further suggests that the person who complies with a request, where social pressure is present, actually ends up feeling good about the asker! How many times have we seen the volunteer fundraiser (or even the paid development officer) that makes an indirect request through innuendo or with hints and negative lead-ins? Ms. Bohns, Assistant Professor at Cornell University encourages a simple direct ask. So, JUST ASK! And if you don’t succeed the first time, go back and ask again, as the first ‘no,’ can sometimes make people more likely to say “yes’ to a subsequent request.

You’re Already More Persuasive than You Think

It’s amazing the opportunities we miss because we doubt our own powers of persuasion.

Our bosses make shortsighted decisions, but we don’t suggest an alternative, figuring they wouldn’t listen anyway. Or we have an idea that would require a group effort, but we don’t try to sell our peers on it, figuring it would be too much of an uphill battle. Even when we need a personal favor, such as coverage for an absence, we avoid asking our colleagues out of fear of rejection.

Yet our bosses and peers would be more receptive to our comments and requests than most of us realize. In fact, in many cases, a simple request or suggestion would be enough to do the trick. We persistently underestimate our influence.

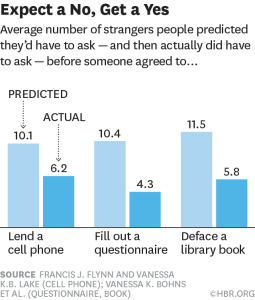

To get a sense of how far off people are in judging their influence, consider a set of experiments I conducted with Frank Flynn of Stanford: First, we asked each research participant to estimate how many people he or she would need to approach before someone agreed to fill out a questionnaire, make a donation to a charity, or let the participant borrow a cell phone.

This disconnect between expectations and reality is a particular problem in the workplace. Because most companies emphasize the rigidity and formality of their hierarchies, employees tend to assume that their influence is dependent upon their roles or titles — that if they lack official clout, they can’t ask for anything.

In research by Frances Milliken of New York University and two colleagues, the majority of 40 employees at knowledge companies reported having concerns about such issues as workflow improvement and ethics — but not speaking up about these issues to their supervisors. The belief that raising the issues would make no difference was the third most frequently cited reason. Said one employee: “Even if I did comment on the issue, it was unlikely to change anything.”

A major part of the problem is that employees tend to forget that managers are people too and that the dynamics affecting all relationships exist even in a boss-subordinate relationship. Bosses care about whether employees respect them, and they feel guilty and embarrassed if they let their direct reports down. However, people generally are unable to put themselves into the mindsets of those on the receiving end of requests. They don’t realize that the social pressure to comply with a request is very, very strong. It’s often harder for people, even bosses, to say “no” than “yes.”

To illustrate, imagine yourself in the following scenario: What would you do if you saw that the president of your company was failing to comply with a simple safety regulation? Would you stand up and ask her to comply? Or would you assume that as president of the company, she would simply brush you off? A team led by Joanne Martin of Stanford report a story of an assembly line worker who got up the nerve to ask her company president, as he was touring the production facilities, to put on his safety goggles. The president’s reaction? He turned “red with embarrassment” and quickly complied. This very human reaction suggests that the same self-conscious emotions and social pressures that drive students in a laboratory to comply with a request to borrow a cell phone affect everyone, right up to the president.

You might assume that if social pressure forces compliance, then succeeding in getting someone to agree to a request amounts to a hollow victory. After all, wouldn’t a person who gave in to social pressure, or was driven to comply out of guilt and embarrassment, end up resenting the asker? But that’s generally not the case.

Like all human beings, people who comply with requests unconsciously generate justifications for their actions. “If I granted this person’s request, I must like him,” is basically how the unspoken thought process works. So rather than feeling resentment, the person who complies with a request ends up feeling good about the asker. In fact, research suggests that the best method for smoothing over a conflict with someone may not be to offer help, but to ask for help. The target of the request is likely to comply, the justification process will follow, and feelings of positivity will start to restore the relationship. Try it. Or consider the coda to the story of the worker who asked the president to put on goggles: The executive eventually returned to tell her how impressed he was with her “guts.”

What this all adds up to is untapped potential: to influence others, to effect change, to blow the whistle on wrongdoing. We don’t venture to transcend our formal roles. We fail to benefit from others’ cooperation.

What happens when people do embrace the influence they didn’t know they had? They ask for things more readily. They don’t worry so much that people are going to refuse their requests. In a sense, they become more powerful — or at least they learn to acknowledge their latent power.

Take the story of Elizabeth, a part-time employee at a major New York City cultural institution whose boss and department head left in the middle of a massive organizational restructuring. Elizabeth herself had the expertise to take on the role, but she had an 8-month-old daughter at home and didn’t want to take on full-time work. Yet, given the organizational climate at the time, Elizabeth was worried that the senior management would simply cut her whole department — and programs she cared deeply about — rather than bring in a new person to run it. She had an idea for what to do, but she wasn’t sure whether the senior management would be willing to consider it. Despite her reservations, she came up with a proposal. She wrote out a job description in which she would take on the responsibilities of maintaining the department’s core programs, with the stipulation that her work hours would never exceed 30 hours a week and would be completely flexible.

The organization’s situation was extremely tenuous at the time, and Elizabeth was nervous approaching senior management with such an unorthodox proposal. “I felt incredibly vulnerable,” she said. But to her surprise, the management team agreed to all of her terms. “It wound up being the best job I could imagine,” Elizabeth said. “I had essentially hand-crafted it to meet my needs and utilize my skills. And I got to take my daughter to the park every afternoon. It was absolutely worth the risk and vulnerability of asking.”

Similar stories emerged when I polled my friends and colleagues — stories of asking one’s boss for a title change, a higher salary, a budget increase, or even just a smart phone — all accompanied by a sense of surprise each time at that magical response: “Yes.”

I find that my research has affected my own behavior: I’ve become more attuned to the things we don’t attempt, out of fear of being rebuffed. Because we’re not attuned to others’ motivation to help us, we limit our ambitions.

I’ve also learned to recognize the responsibility that comes with this latent power. Our words have surprising impact. Not only do we need to be careful about a throwaway comment’s possible unintended consequences — say something negative about someone’s recent absence, and another person in earshot might cancel plans for a needed personal day — but we also have an implied role when we see wrongdoing or room for improvement. Like it or not, we all have a powerful tool for making change: simple direct language.

How does all of this translate into getting what you need when you need it? Research my colleagues and I have conducted offers some practical suggestions on how to make requests.

Just ask. The number one mistake people make is psyching themselves out before even asking for something.

Be direct. Another common mistake is asking indirectly by dropping hints (“Hey Bob, what are you doing this weekend? I’m going to be working on a big project. I wish I had some more help…”). We think we’re being polite by doing so and that people will therefore be more likely to agree to our requests. But my colleagues’ and my research shows that people respond more positively to direct requests. (“Hey Bob, would you mind helping me out with a project this weekend if you have time?”)

Go back and ask again. Another assumption people make is that you shouldn’t ask a person who has previously said “no.” After all, if they said “no” once, they are likely to say “no” again, right? But another line of research by my colleagues and me shows that this assumption is not necessarily true; in fact, saying “no” can sometimes make people more likely to say “yes” to a subsequent request because they feel so guilty about having previously said “no.”

Incentives are not needed. Finally, we tend to think we need to offer someone something in return for a favor — a few dollars for the trouble. However, my research shows that people are just as likely to comply with certain requests for free as they would be in exchange for an incentive. People feel good when they can do something to help someone else out.

We tend to have a lot of misconceptions about influence — how much of it we have, the best way to wield it. Fortunately, the reality is more encouraging than we imagine. The power of a simple, direct request is much greater than we realize.